PHOTO: In recent months there has been a great deal of debate surrounding the “fixed rate mortgage cliff” and its impact on the housing market and the broader economy. FILE

Thousands of Aussie homeowners are rightly concerned about a radical change to their mortgages.

Here’s how badly they might be worse off:

Opinions on the issue range from it being viewed as a relative non-event, to those who view it with far greater levels of concern.

Rather than getting bogged down in the opinions of economists and various commentators, we’ll be looking at a number of different data points from the Reserve Bank, the major banks and other data providers so that you can come to your own conclusions.

The ‘fixed rate mortgage cliff’

The term “fixed rate mortgage cliff” came about to describe the hundreds of thousands of mortgages having their fixed rate terms expire, with those loans to see low fixed rates roll off onto much higher variable rates.

If Westpac’s loan book is broadly representative of the rest of the nation’s mortgages, about 18 per cent of all mortgages overall face coming off low fixed rates on to higher variable rates during this year.

2023 PRICING: Profile YOU on this website! – FOR 12 MONTHS | ONLY $999 plus GST

According to figures provided by the RBA, the average owner-occupier fixed rate loan with a term of three years or under, written between the onset of pandemic to the end of 2021, had an interest rate of 2.14 per cent.

Once November and December’s rate rises have been fully priced into the average variable rate owner-occupier mortgage, the rate payable will be about 5.6 per cent.

While the big four banks all have varying viewpoints on exactly how the cash rate will evolve from here, as things currently stand a majority expect at least two more rate rises.

That would leave the average variable rate for owner-occupiers somewhere in the region of 6.1 per cent.

Many Aussie homeowners will see a hit to their finances when their fixed rate terms expire. Picture NCA NewsWire / Seb Haggett

Insufficient buffers

During the period when the overwhelming majority of these cheap fixed rate mortgages were written, the buffer rate applied by banking regulator APRA was a rate 2.5 per cent higher than the mortgage was written at. This buffer was later increased to 3 per cent in October of 2021.

As things stand today, the average fixed rate borrower faces a 3.46 per cent increase to the rate payable on their mortgage.

For those who took advantage of some of the cheapest loans on offer the figure is closer to a 3.9 per cent increase.

Even with rates as they stand, affected fixed rate mortgage holders face an increase to their mortgage rates far greater than the buffer rates applied by APRA when the loans were written.

The challenge ahead

According to an analysis by the RBA, over 50 per cent of households with a fixed-rate mortgage expiring in 2023 face an increase in mortgage repayments of 40 per cent or more, with rates as they stand today.

Concerningly there are 11 per cent of households in this demographic who will see their repayments rise by more than 60 per cent.

Determining exactly what impact this will have on this selected demographic of households is challenging.

While there are some who took out mortgages at more than six times their household income who now face paying more than 40 per cent of their gross income on their home loan, on the other hand there are households with smaller mortgages that originated years ago who refinanced to a cheap fixed rate loan.

Risks are high for a sizeable minority

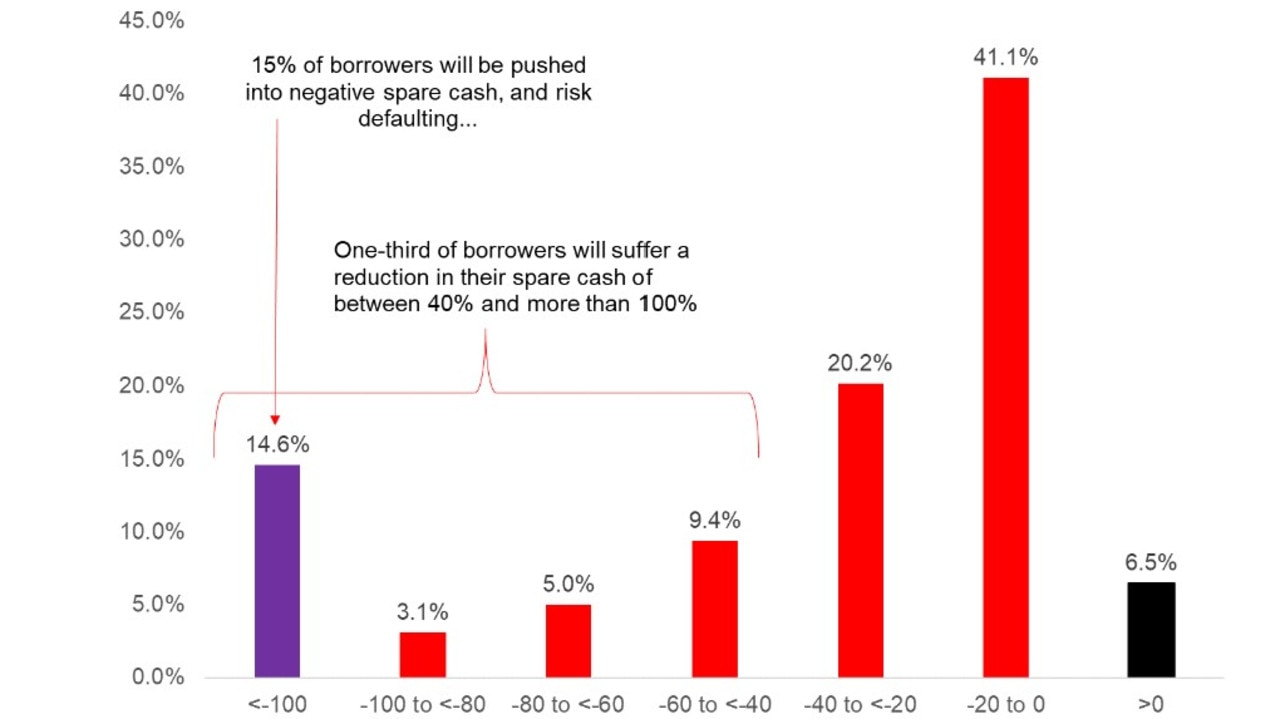

According to a recent analysis from the RBA, at a 3.6 per cent cash rate (two 0.25 per cent increases to the current rate) 14.6 per cent of mortgage holders will have negative levels of household cashflow, leaving them at risk of default.

A further 8.1 per cent will see the level of spare cash in their household budget decline by 60-100 per cent.

An RBA assessment of change in borrower’s spare cash flows after lifting its cash rate to 3.6 per cent. Picture: RBA

On the other side of the coin, 6.5 per cent of borrowers would be completely unaffected by a 3.6 per cent rate, with a further 41.1 per cent seeing their household spare cash drop by 0.20 per cent.

This illustrates nicely that it is not a majority of Aussie mortgage holders who will find themselves in trouble, with many households holding much older and smaller loans that are far less vulnerable to rising interest rates.

That being said, 14.6 per cent of households having negative cash flow is a concerningly large number and more than enough to influence the direction of the property market if enough get into serious trouble.

All of this has happened before …

If this scenario of a large proportion of homeowners seeing their mortgages revert to much higher interest rates sounds familiar, that’s because its all happened before.

In the United States during the Global Financial Crisis, millions of Americans saw cheap “teaser rate” loans expire, pushing borrowers on to much higher variable rates.

This was a major contributing factor to creating the GFC and driving the US housing crash.

In Australia in 2023, lending standards are generally significantly better than they are in the US and its highly unlikely the government and Australian banks will follow the same path as their American counterparts.

In the US during the GFC era, annual home foreclosures peaked at over 923,000, as millions of Americans were driven to the wall by higher rates and the ‘Great Recession’.

In Australia, its arguably more likely that policymakers and the banks will resume a strategy of ‘Extend and Pretend’ if a large number of borrowers get into serious difficulty.

This strategy was employed during the pandemic and effectively allowed borrowers to kick the can down the road through a variety of methods in the hope that they would resume paying their mortgage as normal.

READ MORE VIA NEWS.COM.AU

MOST POPULAR

- Claims about Jacinda Ardern’s wealth

- Real estate agent acted recklessly hugging and kissing a buyer

- Lisa Marie Presley dead at 54 – How did she lose all the Elvis millions? | WATCH

- Real estate agent’s inspection nightmare

- Grand Designs NZ: Off-grid Taylors Mistake house still not finished

- Where have all the property buyers gone?

- Abandoned land for sale

- THE ANCIENT STONE CITY: Proof of NZ civilisation before Kupe

- 2022’s top sale: Herne Bay home sells for $20.75m

- 2022 Australia’s 250 wealthiest individuals | The Rich List